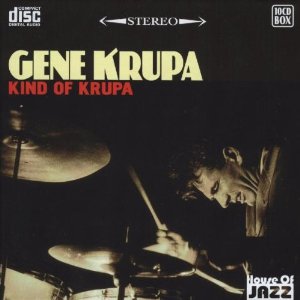

Second, this would have been Karen I. Karr's 59th birthday. Karen was a big fan of Gene, and took pride in the fact they they shared Chicago as their birthplace and home town, and the fact that both were Polish-American. Of course, Karen loved music, so today's post is in the memory of my muse who was all things to me, and a great drummer who inspired me, the generation before me, and subsequent generations of drummers. In the bio pic Swing, Swing, Swing Mel Torme was quoted as saying that the name Krupa would forever be associated with drums. I truly believe that.

About the box set, Kind of Krupa: discs in the set contain tracks spanning the period 1935 through 1959. They span Gene's work in big bands (notably Benny Goodman's and his own orchestras), as well as small ensembles.

The first disc in the set is basically an album simply titled V Discs, which were recorded for the US armed forces in World War II. Here is a sample track:

The next two discs are from two albums featuring drum battles between Gene and Buddy Rich. The first is Krupa and Rich that was recorded in New York in 1955 and features Gene and Buddy on drums backed by the Oscar Peterson Trio (Oscar on piano, Ray Brown on bass and Herb Ellis on guitar), plus Roy Eldridge and Dizzy Gillespie on trumpet, and Illinois Jacquet and Flip Phillips on tenor saxophone (Phillips also plays clarinet. The second is Drum Battle that was recorded live at one of Norman Granz' Jazz At The Philharmonic concerts in Carnegie Hall in New York on September 13, 1952. Musicians include Willie Smith (alto sax) and Hank Jones on piano, and features Ella Fitzgerald on Perdido. Here is a clip from that album, which has a lot more energy than the 1955 studio drum battle:

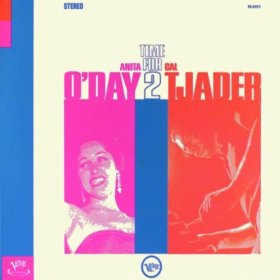

Discs 4 through 7 are comprised of tracks span 1936 through 1949, which include some excellent Anita O'Day performances. In fact, my 26 August 2012 post titled Anita O'Day in depth Part 4 covers some of the source albums for this disc as well as some video clips. The iconic Anita and Roy Eldridge performance of Let Me Off Uptown makes checking out that page worthwhile.

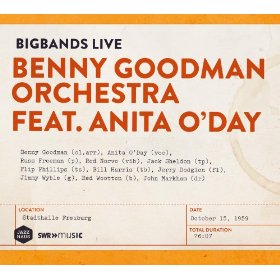

The Benny Goodman years is the focus of disc 8. It contains highlights from his 1935-38 performances with Goodman's big bands, as well as trio and quartet ensembles that featured Gene and Benny with Teddy Wilson on piano in the trio, with Lionel Hampton on vibraphone in the quartet. There are also tracks from the great 1938 Carnegie Hall concert. Here are some representative clips:

The complete album titled Complete Sextet Studio Sessions (featuring Ben Webster & Charlie Shavers) comprises disc 9. The original album was recorded in New York in 1953. Gene on drums is backed by Ben Webster and Eddie 'Lockjaw' Davis on tenor saxophone, Charlie Shavers on trumpet, Bill Harris on trombone, Teddy Wilson on piano and Ray Brown on bass. Unfortunately I do not have a clip to share of this album, but suffice to say, Webster and Shavers make it a treat. If you go to the album link you can listen to sound samples, which are indicative of the great music it contains.

The final disc in the set is the entire 1958 album titled Plays Gerry Mulligan Arrangements. Gerry was an alumni of Gene's big band and served as arranger and conductor for the New York recording session. The big band was comprised of: Al DeRisi, Marky Markowitz, Ernie Royal, Doc Severinsen and Al Stewart on trumpet; Eddie Bert, Billy Byers, Jimmy Cleveland Trombone, Willie Dennis, Urbie Green and Kai Winding on trombone; Sam Marowitz and Phil Woods on alto saxophone; Frank Socolow and Eddie Wasserman on tenor saxophone and Danny Bank on baritone saxophone. The rhythm section was comprised of Gene on drums, Hank Jones on piano, Barry Galbraith on guitar and Jimmy Gannon on bass. Here are some clips from that album:

For more about the set, including a complete track list see my review.

There are some excellent web sites that pay tribute to Gene. One, The Gene Krupa Reference Page has been running for as long as I can remember. If you dig through the pages and links you will find a wealth of information about Gene. Also, the links that are provided to other sites point to even more information that is worth perusing.

I highly recommend the bip pic titled Swing, Swing, Swing as a fairly complete and factual portrayal of Gene's life.

Also of value is this two part interview:

As a parting shot I am including this video titled Gene Krupa and Friends - Legends in Concert. I hope you enjoy it.

The remainder of my day will be spent honoring the memory of Karen I. Karr.