Let's start the journey with a video on the making of Kind of Blue:

Here is an even more in-depth look at the making of the album:

Part 2

Part 3

In the next post, I'll provide an even deeper look at the album.

Deltona, Florida

Let's start the journey with a video on the making of Kind of Blue:

Here is an even more in-depth look at the making of the album:

In the next post, I'll provide an even deeper look at the album.

For the more academically inclined, Gregg Gelb's 1959 Jazz: A Historical Study and Analysis of Jazz and Its Artists and Recordings in 1959 is a fascinating and insightful paper. The next post will focus on the best selling jazz album of all time: Kind of Blue by Miles Davis.

Here is Red Norvo:

Milt Jackson

Lionel Hampton

Terry Gibbs (with the equally great Terry Pollard on both piano and vibes)

A bonus clip of Terry Gibbs, accompanied by Dinah Washington who surprised him and the rest of the band when she joined on on his vibraphone solo (that is Max Roach with the bemused look)

Back to Al Jazzbo Collins: The Ultimate Collection. What a great compilation of the best work of Collins who was the hippest DJ in the San Francisco Bay Area. Or anywhere, for that matter.

This album contains all of Collins' hip fairy tales, but also a collection of great jazz (he was, after all, a jazz DJ.) Some of the music tracks are taken from performances where he was the master of ceremonies, such as "Impressions" - the inspiration for this post - where Don Elliot mimics some of jazz's best vibraphonists, lampooning Red Norvo, Milt Jackson, Lionel Hampton and Terry Gibbs. I would give anything to see the video of that performance because the audience laughs in places that can only be because of on-stage antics. Regardless, the impressions are spot on and, well, the whole thing was hip.

Another gem is on the track titled "Foolin' Around" where Collins introduces Coleman Hawkins at some jazz festival and convinces Hawk to play some warm-up exercises so the audience can hear his tone with no other instruments. Such a serious moment on the album underscores how eclectic this compilation is - and how enjoyable.The real hip stuff, though, comes in his fairly tales (some have Steve Allen on piano), and even the "Bridal Chorus", which was meant to be a serious song, but is the hippest tune ever for taking that walk down the aisle. Actually, it is more like a shotgun wedding. How hip can that be? Enjoy ...

The first is Dizzy Gillespie's Salt Peanuts from the Town Hall, New York City, June 22, 1945. The person who took the time to annotate this clip and post it (along with the other two below)clearly understands music and has excellent critical listening skills. I do need to make one correction to the annotations, which is historical: the drummer identified as Sid Catlett is actually Max Roach. During that concert Sid played on a single song - Hot House - then quickly departed to a gig with Woody Herman. A minor detail. Everything else is spot on. Here is the clip:

The next listening guide is the groundbreaking West End Blues, a Joe Oliver song that Louis Armstrong recorded during his 1928 Hot Fives Session. This was a turning point in jazz on a number of levels. Many of the reasons are evident as you listen to this clip and read the annotations. This song and others from the sessions are available on this album: Louis Armstrong - His 26 Finest Hot Fives & Hot Sevens 1925-1928.

The final song in the listening guide series is Bessie Smith's Backwater Blues. Bessie wrote this song and recorded it on February 17, 1927. This song is on The Essential Bessie Smith. As a side note, James P. Johnson, the pianist, was one of the top three pianists in his era (along with Willie "The Lion" Smith and Thomas "Fats" Waller.) Johnson composed the Jazz Age anthem - The Charleston and was one of the founders of the stride style (along with Smith and Waller.) Here is the Bessie Smith clip:

In my next few posts I am going to discuss the importance of 1959, the year that changed jazz, and the four landmark albums that were released that year.

Jazz Icons: Art Blakey & the Jazz Messengers Live in '58 does the next best thing: it captures that same line-up in a live performance. In fact, being there - even via a video - at a live performance would easily satisfy my wish as a fan.

My favorite segment on this video is Lee Morgan playing Benny Golson's I Remember Clifford. To me that was a musical and emotional high point.

Of course, Bobby Timmons playing his own composition, Moanin', and Merritt's bass solo caught my attention. That segment lasted fifteen minutes and everyone contributed to it being a masterpiece.

No Jazz Messenger performance would be complete without Night in Tunisia. Blakey was absolutely explosive.

Let me preface that this is am amazing video that will please any fan or jazz musician. Now for the quibbles: there is no scene indexing on this DVD. You have one option: play. I can live with that because the booklet that comes with this video far exceeded my expectations for being informative. It, alone, is almost worth the price of the DVD. I was so into this performance that I was disappointed that it ended after only 55 minutes. On the other hand, 55 minutes of Jazz Messenger playing is like triple that of any other ensemble because Blakey's energy and drive spurred on any line-up and pushed them to their limits. In the case of this particular line-up, they put their hearts and soul into it - and it shows.

Here is what you get:

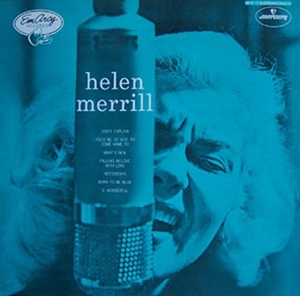

Marc Myers' five part interview of Merrill on JazzWax provided many insights into Merrill, including anecdotes from the 1954 Clifford Brown recording session, and her approach as a musician. And she isn't a vocalist - she is a musician in every sense the same way Anita O'Day was a musician. They both understood how to use their voices as instruments.

What, you are probably asking, does this have to do with drummers? The answer is she emphasizes how important it is to have musicians who connect with her instead of merely accompanying her. During her era, and especially in jazz, the best musicians listened to each other. I recall hearing or reading Papa Jo Jones' advice to do just that too. To illustrate the connection between and among musicians comprising an ensemble, I found a few of Helen's albums that are shining examples and should be closely studied by both drummers and bassists. Especially those who are in groups with vocalists.

The first album is The Duets. Recorded in 1988, Helen's powers are somewhat diminished, but her phrasing and ability to get inside of a song and deliver it are among the reasons I recommend it.

As a music lover, the real power of this album is Helen's skill as a vocalist who - like Anita O'Day - uses her voice as an instrument, and the arrangements by Ron Carter. Indeed, the fact that only Merrill, Carter on bass, and a very subtle Victor See-Yuen on percussion are the ensemble makes this an essential album for musicians. See-Yuen's percussion is so under the music, adding a rhythmic fabric, that Merrill's voice and Carter's bass combine in ways one would have never guessed with such a line-up. This clip is a prime example.

The selection of songs and how Carter arranged them are also reasons why this album works so well. In my quest to learn of and listen to all things Helen Merrill, I came across interviews where she emphasizes many times how important it is to have musicians who connect with her instead of merely accompanying her. Carter's arrangements give that space, and he and See-Yuen do connect with her, as shown by this example.

Listening as a musician I marvel at the way a vocialist and bassist can create an eleven track album that is interesting and enjoyable. It should open the eyes of any small ensemble about the musical possibilities that can be realized. And for bassists, this is like an advanced lesson in melody and groove.

While she will probably be forever remembered for her album with Clifford Brown - surely a masterpiece - her singing on that album only hints at the approach she discusses in her interview.

A study in contrasts can be made by comparing her earlier album with her Homage to Clifford Brown, which is a much different album. Evidence of how different this album is from the original can be heard by listening to one of my favorite tracks from both albums: You'd Be So Nice To Come Home To. Let's compare them:

40 years later

In the original Helen has a presence, but in a more subtle way. She exuded power, but there was another - almost ineffable - quality on that track and the others from that magic session that is vastly different on this one. I am not implying one is better than the other - just that they are different. Part of the reason, I am sure, is Helen had forty additional years of experience that refined her style. And, frankly, she also had forty years of additional age that will alter, for better or worse, a voice.

Differences for whatever reasons do not mask the fact that her phrasing in both are impeccable and she and the musicians with whom she shared the session were connected. Therein lies the lesson. It's not an easy lesson, and perhaps this material is too obscure for many because I have had the advantage of delving deeply into it. The music - even Helen's voice - may be off putting to some. But the interaction between and among the musicians is the key. It's almost like a lost art today. I am offering this set of examples, wrapped in my babbling, as something that merits deep thought and study.

Midnight Blue The (Be)witching Hour contains a number of tracks in slower tempos, and those tempos cover a wide range. Some will probably be inside your playing comfort zone, and others way outside of it. Therein lies the utility of the album (aside from just listening to some great music or even creating a romantic mood for endeavors that go far beyond music and drumming.)

What really inspired me to write about this album is the fact that many if the songs are played with sticks. I am so used to whipping out a pair of brushes for ballads and slower tempo songs that when I tried playing along with sticks earlier it was an embarrassing reminder that I need to practice more ballads with sticks. I'll certainly rectify that shortcoming, but in the meantime, here are some tracks from the album to underscore my comments and to help you to determine if this is an album you need to study.

Coleman Hawkins (with stings and a full orchestra) from track 5

The tempo on the Hawkins' track is one that is well outside my comfort zone.

Dexter Gordon (from track 11 on the album)

Lester Young with the Nat King Cole Trio (from track 13 on the album)

There is not only a range of slow tempos, but some superb music on this album. In addition to being an aid in the study (and mastering) of tempos - especially with sticks - this album also provides a nice starting point for a jazz combo set list. It also doubles as a sure way to create a romantic mood.